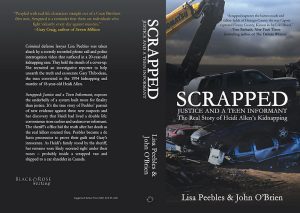

Lisa Peebles is the Federal Public Defender for the Northern District of New York. She and John O’Brien are the authors of Scrapped: Justice and a Teen Informant, released in July 2021.

Lisa Peebles is the Federal Public Defender for the Northern District of New York. She and John O’Brien are the authors of Scrapped: Justice and a Teen Informant, released in July 2021.

The book chronicles the 1994 disappearance of Heidi Allen from an Oswego County convenience store; the trials of Gary Thibodeau and his brother Richard for her kidnapping; and the Federal Public Defender Office’s quest to overturn Gary Thibodeau’s conviction.

Richard Thibodeau was acquitted of Heidi Allen’s kidnapping. His brother Gary was convicted for her kidnapping in 1995, and spent the next 23 years in state prison. Gary Thibodeau died in August 2018, two months after the New York State Court of Appeals affirmed, by a 4-3 vote, the lower courts’ rulings that Gary Thibodeau had not presented newly discovered evidence warranting the vacatur of his conviction.

Lisa Peebles has worked for the Federal Public Defender’s Office for 21 years, and has led it for more than a decade. John O’Brien was a newspaper reporter for The Post-Standard newspaper and Syracuse.com for 30 years, and became an investigator for the Federal Public Defender’s Office in 2017.

In this interview, Lisa Peebles and John O’Brien discussed their respective work on Gary Thibodeau’s case, how and why they wrote the book, and how the Federal Public Defender’s Office came to represent Gary Thibodeau in the first place.

You worked on this case for years. What made you decide to write the book?

Peebles: As we investigated the new evidence and the process that led to Gary’s wrongful conviction, we believed it important to educate the public about the imperfections of our judicial system. It took an emotional toll on me, particularly after Gary died. I felt compelled to share my experience and to share Gary’s tragedy.

O’Brien: As a reporter, I’d never covered a story like this. I was not only writing about what Lisa was uncovering, but was digging up evidence myself that clearly showed a great injustice had been done to Gary. My editors, however, became less willing to let me keep investigating – likely because the DA was frequently complaining to them about my coverage. I thought early on that a book would be the best way to lay out all the new evidence and try to spare someone else from suffering the same awful fate as Gary. Once I became an investigator in Lisa’s office, with a vested interest in ensuring that police and prosecutors didn’t abuse their power, the need to tell the whole story publicly became even greater.

As you were writing the book, what books, movies, podcasts, etc. did you draw on for inspiration or guidance?

We read several true-crime books; I’ll Be Gone in The Dark, Seven Million, Ghost of the Innocent Man, and Just Mercy. We watched Making a Murderer and a host of documentaries about wrongful convictions. Alex Peebles, Lisa’s son, created a podcast about the case that inspired our final push to finish the book.

Because you co-authored the book, how did the writing process work? And how long did the writing process take?

We drafted chapter outlines to guide our writing. We attended a writing workshop and solicited feedback on how best to tell our story. We decided to write individual chapters in the first person so the reader would know who was speaking. For each chapter, we worked off each other’s draft to add to, edit and improve it. We discussed every aspect of the case ad nauseum. We had multiple editors. It took more than four years to write the book.

Have you received any feedback on the book from law enforcement or from the family of Heidi Allen?

We’ve had positive feedback from law enforcement if they were not part of the Oswego County Sheriff’s Office or District Attorney’s Office. Heidi’s cousin supported our efforts and gave us a favorable review of the book. No one else from the family has said a word.

How did the Federal Public Defender’s Office come to represent a man seeking to overturn a state murder conviction? And is that kind of representation common?

I hired Randi Bianco as an assistant federal public defender in 2013. A woman tried contacting Randi about evidence that would exonerate an old client of hers, Gary Thibodeau. Randi had represented Gary throughout his state court appeals and a federal habeas petition. Gary exhausted and lost all his appellate avenues. When the woman couldn’t reach Randi, she was diverted to the Oswego County district attorney by the lawyer who bought Randi’s private practice. Randi learned about the woman and pressured the DA to tell her about the new evidence. We eventually discovered there was Brady material that should have been turned over to the defense.

We asked Chief U.S. District Judge Gary Sharpe if he would appoint our office to represent Gary in a successive federal habeas petition. He agreed, but we were required to exhaust his state court remedies first. This is not common in our district, but there are many federal defender offices in the country that have separate non-capital habeas units. Many of those cases require appearances in state court for ancillary proceedings.

If Gary Thibodeau were alive today, what do you think would be the status of his post-conviction relief efforts?

We petitioned the New York State Court of Appeals for a rehearing after we reviewed the 4-3 decision upholding the lower court’s decision. We believed there were misstatements of fact forming the basis for the adverse ruling. Gary died before we were granted a rehearing. If that avenue hadn’t worked, we were positioned to file a successive federal habeas petition based on a Brady violation. Senior U.S. District Judge Thomas J. McAvoy ruled against Gary on his first federal habeas petition in 2007, before the additional evidence surfaced that would have formed the basis of the second habeas petition.

What lessons does this case have for the legal profession?

It showed that our system is imperfect, that without DNA evidence, it’s extremely difficult to obtain relief for someone who was wrongfully convicted; that community pressure can influence and steer the direction of an investigation; that our institutions are geared more for maintaining finality than truth-seeking; and that we cannot be complacent in our respective roles. It is incumbent upon all of us, defense attorneys included, to conduct our own thorough investigation, and not to assume something is true just because someone says it is.